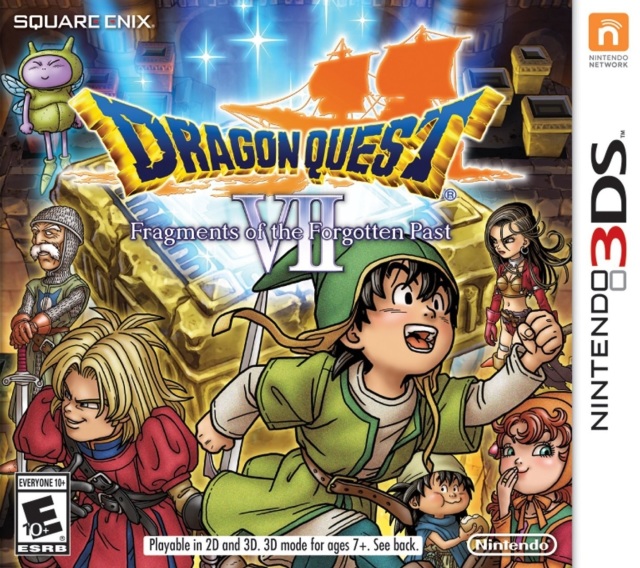

Dragon Quest VII: Fragments of the Forgotten Past

The only island in the world…or is it?

One of the final RPGs I played for the Sony PlayStation was Enix’s Dragon Warrior VII, titled Dragon Quest VII: Warriors of Eden in Japan, which was the first entry of the series I played on a console since the original Dragon Warrior on the Nintendo Entertainment System. Throughout the 2000s, the franchise would undergo a translational renaissance in the West, culminating in retaining the Dragon Quest name outside Japan. However, success in the Anglophone world would vary drastically. Thus, the seventh Dragon Quest remake for the Nintendo 3DS seemed doomed to remain in Japan when released in the next decade. Mercifully, it would be rescued and localized as Dragon Quest VII: Fragments of the Forgotten Past.

The rerelease opens on Estard, the only island in the world, with the protagonist, the son of a fisherman and his wife, working with Prince Kiefer, the kingdom’s reluctant heir, to delve into the world’s mysteries, which may lead to clues as to why their isle is all alone in the first place. The town mayor’s daughter, Maribel, joins them, with the party getting the help of individuals like the scholar Dermot the Hermit to investigate the Shrine of Mysteries, populated with pedestals that can contain the subtitular fragments scattered across Estard, which hold the key to their world’s “forgotten past.”

The scenarios the hero and his allies encounter throughout the game are endearing, developed well, have backstories, and explain why Estard seems all alone. Some texts from bookshelves add background and philosophy, with many relatable themes abounding, like unsupportive parents, rewriting history, burying inconvenient historical facts, etc. While the periods and connections between past and present scenarios aren’t always explicit, they are still intriguing. Drawbacks include glacial pacing, methodical story structure, predictable and derivative plot points, and vague narrative direction. Regardless, the narrative is an excellent draw to the game.

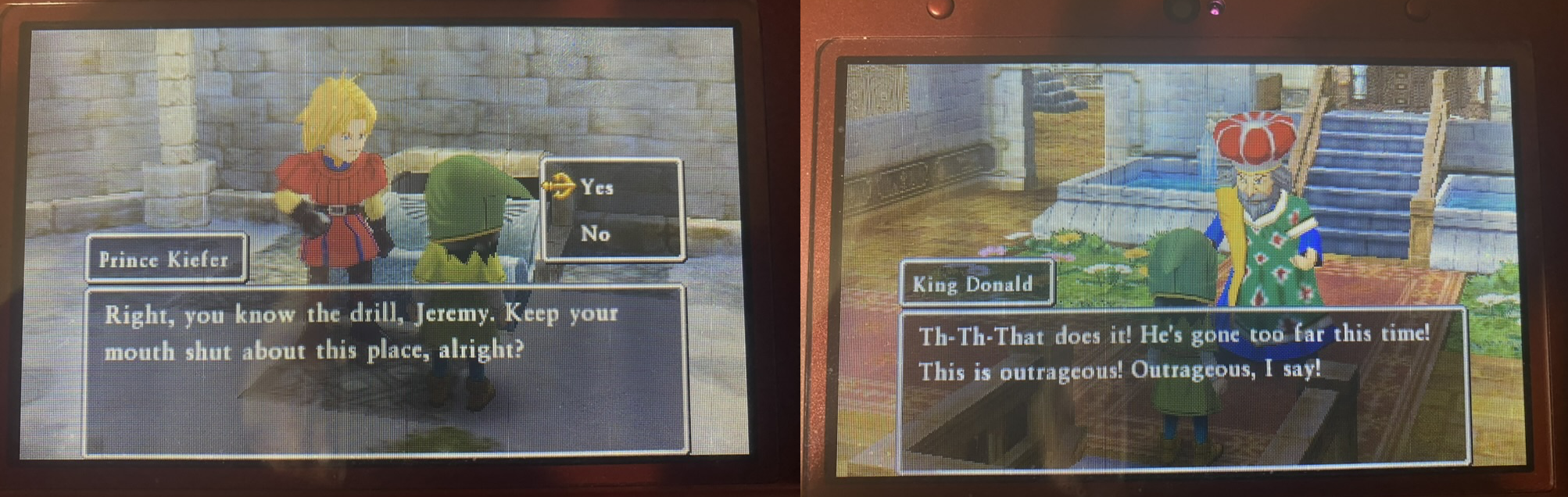

The localization, characteristic of previous series entries translated into English, breathes life into the dialogue, with the PlayStation version’s script having amounted to more than ten thousand pages, which could have explained the long translation period. Regional dialects return in full force, representing linguistic groups like the English (Renaissance and contemporary), Scottish, British, Cockney, French, Germans, Russians, and more. Clever naming conventions also abound, like renaming Prince Kiefer’s father King Donald in honor of the Sutherlands, numerous pun-based identities for individuals and enemies that include Cardinal Sin, Dermot the Hermit, the forky pig, the tongue fu fighter, etc.

However, the translation retains countless irritating conventions of Japanese RPG dialogue, including a chronic overuse of exclamation points and ellipses, spelled-out laughter (like “ha, ha, ha,” which today only sounds natural if done sarcastically), other onomatopoeia rendered in English (like sleepers saying “Ah-phew! Ah-phew!”), and so forth. Occasional awkward dialogue abounds as well, which encompasses the franchise’s staple encounter quote “But the enemies are too stunned to move!”, and a few punctuation marks are misplaced. There’s also maybe one inconsistent spelling of a character’s name (Autonymous instead of Autonymus), but the localization overall shines.

As a testament to the glacial pacing, players don’t encounter their first enemies until over an hour into the narrative. However, the tempo of the game mechanics beats in the opposite direction. At first, they seem like standard Dragon Quest: the player inputs commands among up to four characters, like attacks with equipped weapons, defense to reduce damage, MP-consuming magic, or various skills that may or may not require MP. The standard rules of traditional turn-based Japanese RPG combat exist, with characters and the enemy, after the players input their party’s orders, exchanging commands in an order allegedly depending upon agility, but this can be random and lead to occasional incidents of things like healing allies low on HP coming too late.

The player can attempt escape from combat, but as with 99.99% of JRPGs (except maybe Chrono Cross), this doesn’t work all the time. Other features include AI options for all characters except the protagonist (alongside a manual selection of orders), which players can set for individual allies or the entire party. These include not using MP when selecting commands, going medieval against enemies, focusing on keeping HP high, and emphasizing stat-boosting abilities and defense. While AI, of course, can often be artificially incompetent, I found this handy (especially “Don’t Use Magic,” since dozens of excellent free skills come later in the game), and methinks it shaved a few hours off my total playtime than if I had always selected skills myself.

Victory results in all characters still alive acquiring experience for occasional leveling, money, and occasional items. I should add that the remake ditches random encounters (except in one late-game dungeon, the Multipleximus Maximus) in favor of visible enemies, who charge the player’s party when their levels are lower than or equal to theirs and run away otherwise. One spell, Holy Protection, can temporarily make enemies on fields and in dungeons other than those higher in level disappear, nullifying the possibility of accidentally bumping into weaker foes. The difficulty for the first part of the game was fair for me, and I often needed to use consumable healing items in a few tough boss battles.

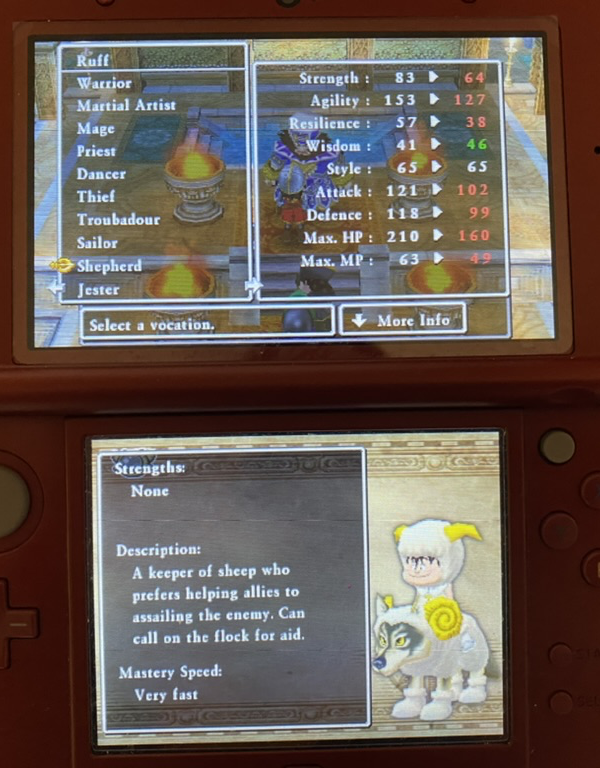

When the player unlocks Alltrades Abbey (after Kiefer leaves your party permanently, so don’t waste stat-increasing seeds on him or worry about constantly upgrading his equipment), the fun truly begins. Then, players access an engrossing class system, with their party able to select from many base vocations; mastery of these unlocks those of higher tiers. Every class increases and decreases all a character’s stats by a certain amount. Fortunately, players need not keep tons of spare equipment available for job changes like Final Fantasy V. As in Dragon Warrior VII, characters acquire experience for their vocation after triumphing in an enemy encounter, but only if the foes’ levels are on par with or higher than theirs.

One improvement over the PlayStation version is that class levels rise quicker, but at the same time, characters can now only access abilities in intermediate and advanced classes if in the former or the latter if the middle-tier classes are prerequisites for those upper-tier. Monster classes from the original return (their respective hearts acquired from treasure chests or battle) and allow them to transform into these adversarial vocations to learn their skills. Unlike Dragon Warrior VII, enemy vocations are no longer divided into a hierarchy, with all skills learned from them remaining with the allies who learn them regardless of their current job.

Returning to the matter of free skills, which characters will learn frequently, many can be incredibly useful, like Hatchet Man, which has a 50/50 chance of dealing unblockable critical damage to enemies and can be handy at making mincemeat (or mincegoo) of metallic slime foes that run away quickly but reward ludicrous experience when killed. However, this can be a double-edged sword since it can consequentially level characters to the point where they don’t advance in their classes (but in most late-game areas, enemies will reward class experience regardless of strength or weakness).

To sum up, the game mechanics work surprisingly well, especially with the pacing of combat contradicting that of the narrative. I could end most standard battles on the highest speed setting within a round or two without half a minute passing. Furthermore, with character class paths planned carefully, I blazed through the final boss fight without dying. However, many issues from prior series entries recur, like the inability to target specific enemies in groups, the randomization, no telling of when beneficial spells (except Oomph) expire, and the AI not being foolproof. Late-game, furthermore, when the player has five party members, the extra can’t come along, which is a step down from previous installments where one could have everyone and switch them in and out of battle on the fly from reserve.

Control has rarely been a strong suit in the Dragon Quest series, and the seventh entry’s remake continues that trend. Endless dialogue and confirmations when performing simple tasks like shopping and saving your game? Check. Frequent vague direction on advancing the main storyline, even when talking to everyone? Check. Needing constantly to reference the internet regarding said poor direction and other things like hidden secrets and puzzles? Check. However, conveniences like instant teleportation among visited towns and exiting dungeons return, though these have issues, with the former only working in the present and the latter not always readily available. Furthermore, when acquiring the second nautical ship late-game, I couldn’t figure out how to get off the thing without using Zoom to a town, and the in-game clock was slow.

Even so, the fragment finder, which indicates whenever the subtitular fragments are nearby, is the best improvement over the PlayStation version. The fairy at the Shrine of Mysteries also often clues players about the location of the next one necessary to access a new area in the past. However, this did fail me at one point later in the game since I had to talk to a nonplayer character to get the detector to work in a respective area. Other improvements include maps for towns and dungeons (but in their case, players can’t swap among maps within and without floors to see how they’re connected) and an always-convenient suspend save in case reality calls. Overall, the interaction aspect doesn’t fail miserably but could have been far better.

The late Koichi Sugiyama’s soundtrack, gloriously orchestrated in the remake, excels as always, with the return of the standard series overture, staple franchise tracks such as the save menu theme, and others that fit the various moods and settings. However, many moments are without music, and the franchise’s dated sound effects return in full force.

The remake’s visuals are far better than those in Dragon Warrior VII, fully rendered in three dimensions and taking advantage of the Nintendo 3DS’s glasses-free 3-D capabilities. The environments have vibrant hues (but frequent blurry and pixilated textures, characteristic of most three-dimensional graphics), and the illumination effects are superb. The character models fit the late Akira Toriyama’s character designs, including lip animations (but facial expressions mostly remain happy), and different vocations yield alternate costumes for the player’s party. However, Toriyama’s standard enemy reskins commonly recur, horrible collision detection abounds, and environmental elements frequently, abruptly, and unnaturally appear during overworld navigation. Regardless, the 3DS version’s graphics are a sight to behold.

Finally, finishing the main quest can take players as little as sixty hours (my final playtime clocked somewhere over eighty), with sidequests galore like countless subplots, completing the monster compendium, and two postgame dungeons, which can pad playtime further. However, the game excessively overstays its welcome, with other detriments to lasting appeal like fixed difficulty, minimal narrative variations, no New Game+, and the constant need to reference the internet to complete anything and everything.

With tight and enjoyable game mechanics, an intriguing narrative, and solid audiovisual presentation, Dragon Quest VII on the Nintendo 3DS is both an excellent remake and one of the far better entries of a series whose quality has ranged from okay to decent. However, issues like the need for foresight in character class path planning, retained dated series traditions, and glacial and vague narrative direction detain it from masterpiece status. Regardless, I enjoyed the time I spent with the game and wish others the same positive experience. Lamentably, events like the Nintendo 3DS eShop’s closure and the worldwide gaming industry’s apathy towards the preservation of video game history (enforced by American groups like the Entertainment Software Association) have made herculean the capacity to play it affordably and legally, but if it ever receives an enhanced port or secondary remake (provided they don’t screw things up), pick it up.

This review is based on a playthrough of a digital copy purchased and downloaded to the reviewer’s Nintendo 3DS to the standard ending, with none of the postgame content experienced.

| Score Breakdown | |

|---|---|

| The Good | The Bad |

| One of the best, if not the best, JRPG class systems. Engaging substories, with endearing localization. Excellent soundtrack. Visuals are a million times better than the PlayStation version’s. | Character class planning requires some foresight. Retains franchise’s dated traditions. Incredibly glacial narrative pacing and vague direction. Good luck finding it at a reasonable price. |

| The Bottom Line | |

| An excellent remake, but terrible narrative direction and overstaying its welcome prevent it from masterpiece status. | |

| Platform | Nintendo 3DS |

| Game Mechanics | 9.0/10 |

| Control | 6.5/10 |

| Story | 9.0/10 |

| Localization | 9.0/10 |

| Aurals | 9.5/10 |

| Visuals | 8.5/10 |

| Lasting Appeal | 6.0/10 |

| Difficulty | Easy to Moderate |

| Playtime | 60-120 Hours |

| Overall: 8.5/10 | |